"The past actually happened, but history is only what someone wrote down." - A. Whitney Brown

Monday, April 25, 2016

Anzac Day

Today marks the one hundredth anniversary of Anzac day, which was established on the first anniversary of the landing of the Anzac troops in Gallipoli during the First World War (though unofficial commemorations had begun almost immediately after Gallipoli).

Here's the Stuff You Missed in History Class episode about Gallipoli. And if you're interested, on AcornTV they have the Anzac Girls miniseries.

Monday, April 18, 2016

Monday, April 11, 2016

Mulready Stationery

I’m back

with a real post this week! Yay!

Last night

I finished reading The Brontë Cabinet by Deborah Lutz, which I highly

recommend. It’s a joint biography of the

Brontës through nine items. One of the

items was a letter Charlotte had written which had been torn apart and sewn

back together. The chapter about letters

discussed them more broadly; the torn one was just a small part of the

chapter. In talking about letters, Lutz

went briefly into the history of the postal system and different types of items

that were used by the Brontës. One of

the items mentioned was Mulready stationery.

This is

probably going to be a shorter post since Mulreadys didn’t last long, so a bit

of background on what was going on with postage at the time. Before 1840 (when postal reforms went into

effect), in England, postage was paid by the sheet of paper, with the envelope

counting as a piece of paper; was paid by the mileage the item had to travel;

and was paid by the recipient of the mail.

In 1840,

postal reform took place. Both stamps

and letter sheets were introduced.

Stamps were what you think they are, a small square you could stick on

any item going through the mail, as long as it had enough postage. Letter sheets were preprinted and prepaid

sheets of paper that would be folded up to create the letter and the envelope

in one. If you’ve ever used or seen air

mail sheets, the letter sheets were like that.

William

Mulready was the person who came up with the design that was printed on the

letter sheets. Mulready was a well-known

Irish artist, living in London at this time.

He was commissioned to create the illustrations for the letter

sheets. His illustrations had Britannia

at the top and center; on either side were symbols of Asia and North America,

showing the reach of the British Empire.

The illustration also showed that the mail was prepaid, with different

colors of ink being used for different postage: black for one penny, blue for

two penny. Because they were just blue

or black inked images, a lot of people hand-colored them in.

Rowland

Hill was a postal officer and one of the men who helped with postal

reform. He was sure that stamps would be

a folly and that Mulready stationery would take over. However, almost immediately it became

apparent that people preferred stamps.

Mulready’s design was overly complex and was mocked and caricatured

almost immediately. Stationery creators

and sellers also didn’t like it because then they couldn’t sell their product,

whereas stamps could be used on anything.

People thought the government was trying to control the supply of

envelopes by developing the letter sheets, too.

Mulready

stationery went on sale May 1, and was valid in the mail starting on May

6. By May 12, Hill realized it wasn’t

going well, and within two months the stationery was being replaced by more and

different stamps. The supply of Mulreadys

that were in shops were used until they were gone, but distributors weren’t

distributing them anymore. What was left

of the Mulreadys were destroyed, eventually having the middles punched out so

the part without printing could be reused.

These middles were sold as waste paper or were recycled.

So that’s

it about Mulready stationery. They only

lasted from May to November 1840.

They’re such an interesting part of postal reform and history; I’m

surprised I haven’t come across them before.

Monday, April 4, 2016

Just pictures...

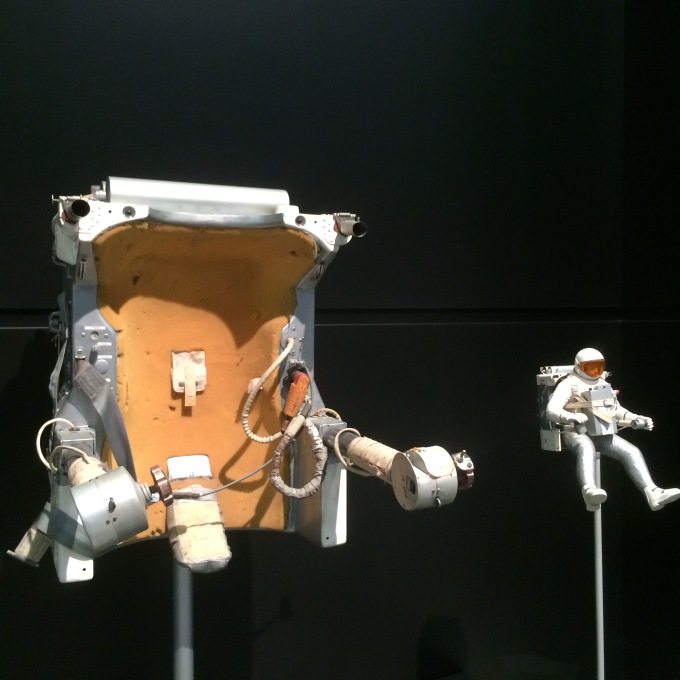

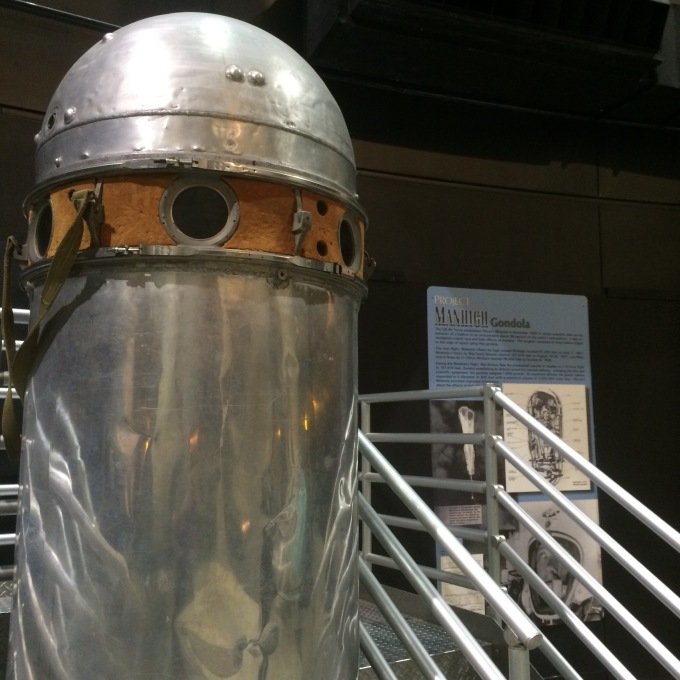

So, no post last week... Sorry. Between the holiday - meaning travel - and then a work field trip, it just didn't happen. It also isn't really happening today. I'm working on something for work (that I will share here too when it's done) and so don't have anything today. But I do have photos of last week's said field trip.

We have a contest at work and if we hit such and such a milestone we get a field trip. Last Monday we went to Wright Patterson Air Force Base Museum near Dayton. Here a few photos from the trip.

Monday, March 21, 2016

The Cottingley Fairies

I’m not sure why it’s taken me so long to pick this

subject. I’ve been interested in the Cottingley

Fairy story since FairyTale: A True Story

came out in 1997 (I would’ve guessed it was earlier than that, actually). It just ticks all the right boxes for me: the

right era, fairies, photos, a hoax. It’s

just great. Like I said, I should’ve

done this post earlier.

In 1917,

Frances Griffiths and her mother went to live with her aunt, uncle, and

cousins, the Wrights, in Cottingley, near Bradford, in England. Frances had grown up in South Africa, but due

to World War One, her father was now in the army and she and her mother had to

go live with family. Frances was about

ten, and her cousin, Elsie, was about sixteen.

They played together down by the Cottingley beck (stream) and would

often come back filthy, much to their parents chagrin. They claimed they were down at the beck

playing with fairies. One Saturday, they

decided to borrow Arthur Wright’s Midg camera and “take a photo of the fairies

they had been playing with all morning” (1).

They came

back from the beck a picture of Frances and some fairies. Arthur knew that Elsie was an artist and

liked drawing fairies and so thought the photo was faked somehow. About a month later the girls borrowed the

camera again and came back with a picture of Elsie and a gnome. Again, Arthur thought it was faked, and didn’t

let the girls borrow his camera anymore.

Polly Wright, though, believed her daughter’s and niece’s photos were

real.

In mid-1919, Polly took the photos

to a theosophy meeting. Theosophy

believes in finding divinity in the mysteries of nature. Theosophy also believes that humanity is

evolving towards perfection. The photos fit

in with these beliefs because they showed people being able to interact with “higher

beings”, that were one of those mysteries of nature.

Polly

showed the photos to the speaker at the theosophy meeting, asking if they might

be real; the speaker took them and showed them at the society’s conference a

few months later. At this conference

Edward Gardner became interested in the photos.

Gardner sent the photos to the photographic expert Harold Snelling. Snelling believed the negatives were

authentic in that they photographed what was in front of them; he wouldn’t

comment if the fairies were real though.

Gardner had Snelling clean up the negatives so they could be better

printed and better analyzed. Gardner

sold the prints at his lectures. The

photos quickly spread through the spiritualist community.

The photos

were gaining an audience. In 1920, Sir

Arthur Conan Doyle heard of the photos from the editor of Light, a spiritualist publication.

Doyle had long been interested in mysticism and spiritualism; after the

deaths of his wife, son, brother, brothers-in-law, and nephews all in a fairly

short span, this interest deepened.

Doyle contacted Gardner about the photos to find out more about

them. Doyle then contacted Arthur and

Elsie Wright, asking their permission to use the photos for an article he was

writing. Arthur agreed, but didn’t want

to be paid for their use believing “if genuine, the images should not be ‘soiled’

by money” (3).

Gardner was

still trying to prove the authenticity of the photos. He went to Kodak for a second opinion. Kodak said the photos “showed no signs of

being faked” but that “this could not be taken as conclusive evidence … that

they were authentic photographs of fairies” and wouldn’t give a certificate of

authenticity to them (4). The

photographic company Ilford also believed there was evidence of faking. Doyle, too, was seeing if other people

thought they were real. He showed the

photos to the psychical researcher Sir Oliver Lodge. Lodge believed they were fake, sighting their

“distinctly ‘Parisienne’ hairstyles” (5).

In July

1920, Gardner went to Cottingley. He

brought two Kodak cameras and “secretly marked photographic plates” and wanted

Elsie and Frances to take more photos (6).

By this time Frances was living in Scarborough with her parents, but she

was invited back for the summer. The

weather was bad that summer and it wasn’t until August 19 that they were able

to take more photos. Polly Wright was

with the girls, but they told her the fairies wouldn’t come out if others were

around, so Mrs. Wright left. The girls

were then able to take three new photos.

The new

photos were carefully packaged and sent to Gardner in London. Gardner was thrilled with the pictures and

sent a telegram to this effect to Doyle who was lecturing in Australia. Doyle replied, “When our fairies are admitted

other psychic phenomena will find a more ready acceptance” (7).

The article

Doyle had been working on, and used the photos for, came out in The Strand around Christmas 1920. The issue sold out in two days. In the article, the Wrights were called the Carpenters,

Elsie was called Iris, and Frances was called Alice. Press coverage of Doyle’s article was mixed,

but with a lot of “embarrassment and puzzlement” (8).

In 1921,

Doyle wrote another article for The

Strand about other accounts of fairy sightings. These articles formed the basis for his 1922

book, The Coming of the Fairies. The second article and the book, too, had mixed

receptions.

In 1921,

Gardner made his last trip to Cottingley.

Again he brought cameras and photographic plates, but he also brought the

clairvoyant, Geoffrey Hodson. This time

the girls didn’t see any fairies and no photos were taken, but Hodson took a

lot of notes about all the fairies he saw around. By this point Elsie and Frances were tired of

the fairies and just played along with Hodson “out of mischief” (9). The girls grew up, married, and moved abroad,

the Cottingley fairies left behind them.

While

mostly fading from view, the photos still popped up after this. In 1945 Gardner’s book, Fairies: The Cottingley Photographs and Their Sequel, was

published. Still, criticisms

persisted. People said they looked like

paper cutouts and that people just needed something to believe in after the

war.

In 1966, the Daily Express found Elsie back in England and interviewed her. She said maybe the fairies were just her

imagination and maybe she’d found a way to photograph her thoughts. This interview renewed interest in the

photos. In 1971, Elsie was interviewed

on the television program Nationwide,

and said the same thing as 1966. In 1976,

Elsie and Frances were interviewed together.

They said “a rational person doesn’t see fairies” but still said the

photographs were real (10).

In 1978 James Randi investigated

the photos. He found the fairies looked

very similar to images in Princess Mary’s

Gift Book, which came out in 1915.

In 1982-83, Geoffrey Crawley, the editor of the British Journal of Photography, came out saying the photos were

fakes.

In 1983 in The Unexplained magazine, Elsie admitted the fairies were faked to

Joe Cooper. She admitted that they were

drawings and that hatpins were used to hold them in place. She still claimed that they had seen fairies

and only the ones in the photos weren’t real.

Frances admitted to the fakes as well. However Elsie said all five photos were faked,

while Frances claimed the fifth one was real.

In 1985, on Arthur C. Clarke’s

World of Strange Powers, Elsie expanded, saying that once Doyle was brought

in, believing in the photos, she and Frances were too embarrassed to tell the

truth. Frances said, “it was just Elsie

and I having a bit of fun – and I can’t understand why they were taken in –

they wanted to be taken in” (11).

Frances died in 1986 and Elsie died

in 1988, both not long after they came clean.

Interest in the photos continued though.

In 1998 prints, a first edition of The

Coming of the Fairies, and some other items were auctioned off for

£21,620. Also in 1998, Geoffrey Crawley

sold off all the Cottingley things he had acquired; this included prints, two

of the cameras, fairy watercolors Elsie did, and a letter in which Elsie

admitted the hoax. Crawley sold the

items to the, now called, National Media Museum in Bradford (near Cottingley).

In 2001, some of the glass plates

were auctioned for £6,000 to an unnamed buyer.

In 2009, Frances’s daughter went on Britain’s Antiques Roadshow with some of the photos and one of the cameras

from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. She, like

her mother, believed the fifth photo was real.

Her items were appraised at £25,000-£30,000. Later in 2009 Frances’s memoirs were

published.

In 1994, Terry Jones and Brian

Froud parodied Cottingley in Lady

Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book. In

1997 two movies related to Cottingley came out: FairyTale: A True Story and Photographing

Fairies.

The lure of

the fairies continues… I think part of

it is the wonder and mystery, but also how someone like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

believed in them. I think it also tells

you something about the time period that the photos became so popular and had

both believers and skeptics.

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 - Cottingley Fairies

Monday, March 14, 2016

Where'd the week go?

Well, I completely lost track of the days this week and don't have a new post. I thought I'd share an article I read recently, though. It's peripherally related to the Victorian fabric dye article, and so I thought it might be of interest. Enjoy!

Also, Happy Pi day!

Monday, March 7, 2016

Violet Oakley

Back in

2010 my family took a trip to Philadelphia.

On the way we stopped in Harrisburg and went to the Capitol building (we’d

go to any capitol building we could when on vacation). One of the first things you notice about the capitol

is the gorgeous green dome. When you

enter the building it’s just as gorgeous.

A big part of what makes Pennsylvania’s capitol special is the murals

throughout. The murals were done by

Violet Oakley, the first American woman to receive a public mural commission.

Violet

Oakley was born on June 10, 1874 in Bergen Heights, New Jersey (her birthplace

is often listed as Jersey City; Bergen Heights was part of Jersey City, so

neither is wrong). Both of Violet’s

grandfathers were members of the National Academy of Design, so when Violet

wanted to be an artist, she had a relatively easy path. In 1892 she started at the Art Students

League of New York, and the following year went to study in England and France. In France she studied at the Académie

Montparnasse.

In 1896

Violet returned to the US to study. She

began at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, but less than a year later

she left and transferred to the Drexel Institute School of Illustration after

the urging of her sister, Hester, who was already attending Drexel. At Drexel, Violet studied under Howard

Pyle. At this time she also made friends

with Elizabeth Shippen Green and Jessie Willcox Smith, other students of Pyle’s;

Pyle nicknamed them the Red Rose Girls because they lived together at the Red

Rose Inn (1).

Violet had

success as an illustrator. She had

pieces in The Century Magazine, Collier’s

Weekly, St. Nicholas Magazine, and Women’s

Home Companion. At the time, about

88% of subscribers to magazines were women, and so there was a push to show the

world from a woman’s perspective, and so women were hired as illustrators. (2).

Despite the success at

illustration, and teaching her illustration, Pyle actually encouraged Violet to

pursue large scale pieces and helped Violet get commissions for murals and

stained glass pieces. Violet still

worked on small pieces when she could.

Violet

attributed her style to Pyle and to the Pre-Raphaelites. Her art also showed a “commitment to

Victorian aesthetics during the advent of Modernism” (3). Violet had also become a Quaker in her adult

life (she was raised Episcopalian), and wanted to showcase the Quaker ideals of

pacifism, equality of races and sexes, and economic and social justice (4).

In 1902,

architect Joseph M. Huston chose Violet to create murals for the Governor’s

Reception Room in the state capitol in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, purely on the

basis of her talent (5). Before this

point, her only mural had been at the All Angels Episcopal Church in New York

City. Violet admired William Penn’s

utopian vision for Pennsylvania, and wanted to highlight this. She travelled to Europe to study about Penn’s

life. The murals in the Reception Room

took Violet over four years, and highlight her talents as well as her interest

in history. Violet would do fourteen

murals total for the Reception Room, and 43 murals in total in the Capitol

building.

In 1903,

while she was working on these murals, Violet joined Christian Science. While she had been in Florence, Violet had

her asthma cured through prayer and so joined Christian Science. She was a member of the Second Church of

Christ, Scientist in Philadelphia from its founding in 1912 until her death in

1961. In 1939, Violet even illustrated a

poem by Mary Baker Eddy (the founder of Christian Science) in the style of

illuminated manuscripts.

In 1911,

Violet was working with Edwin Austin Abbey on the Senate Chamber and Supreme

Court Rooms at the Capitol, when Abbey died.

Due to her talent and work with Abbey, Violet was chosen to finish Abbey’s

work. This work took Violet nineteen

years, over which time she completed the murals, six illuminated manuscripts,

and a book about the murals.

After her

work at the Pennsylvania Capitol, Violet did a mural at the League of Nations

Headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland; the Henry Memorial Library at the Chestnut

Hill Academy in Philadelphia; and the First Presbyterian Church in Germantown

in Philadelphia (6).

Throughout

the rest of her life lived on and off with the Red Rose Girls and Henrietta

Cozens. Their home in Mt. Airy, PA was

called Cogs from their initials (Cozens, Oakley, Green, and Smith). The home was later called Cogslea, and was

placed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Violet Oakley Studio

in 1977. Her home and studio in Yonkers,

NY, where she lived on and off from 1912 to 1915, are also in the National

Register as Plashbourne Estate.

Violet

lived at Cogslea with her longtime companion Edith Emerson after the other Red

Rose Girls moved out. Edith was the

director and president of the Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia. They lived together for the rest of their

lives. Violet Oakley died on February

25, 1961. She is buried in the Oakley

family plot in Green-Wood Cemetery.

While

Violet’s work had fallen out of favor after World War II, there was renewed

interest starting in the 1970s. In 1996,

Violet Oakley was inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame - the

last of the Red Rose Girls to be inducted.

In June 2014, Violet’s grave was featured on the first gay themed tour

of Green-Wood Cemetery (7).

1, 2, 3, 4, 7 - Violet Oakley

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)